UNA PRESENTAZIONE DELLA RIFORMA ITALIANA DEL 2014-2015, MIRATA A EVIDENZIARNE PER GLI OSSERVATORI STRANIERI I PRINCIPI ISPIRATORI, LA LOGICA COMPLESSIVA E LE DISPOSIZIONI DI MAGGIORE RILIEVO

Articolo pubblicato nel n. 3/2016 del CESifo DICE Report [1], settembre 2016 (il testo è stato licenziato nel giugno 2016) – Sui contenuti della legge-delega n. 183/2014 e dei decreti attuativi, nonché il dibattito in proposito, v. anche i documenti resi direttamente accessibili dal Portale della riforma del lavoro [2]

Summary

1. Sharpness and significance of this breakthrough

2. The new rules on dismissals

3. Overcoming the disparity between protected and unprotected employees

4. Employees’ protection in the market, not against the market

5. The so-called Repositioning Agreement as a tool to shorten unemployment spells

6.The new provisions governing change of duties and marking the distinction between subordinate employment and free-lance collaborations covered by the Civil Code

7. The most significant issues of compliance with the Constitution: a) regarding the difference between the discipline of ongoing contracts and the discipline of new ones

8. Continued: b) regarding the replacement of the property rule that has protected regular workers so far, by a liability rule, and the reduction of Court-ordered indemnification; c) regarding the use of the predetermined severance cost as an objective sorting tool for business decision in this regard

9. Impact of the reform on employment flows and quality in the first year

10. Hypothesis about the impact of the economic shock versus the regulatory shock

-

Sharpness and significance of this breakthrough

Sharpness and significance of this breakthrough

The 2015 reform changed Italian labour law more significantly, we may say, than the one of May 1970, when the Statuto dei Lavoratori was enacted (a very important reform of the entire discipline of individual and collective labor relations, which introduced some very important protections against dismissal and discrimination in the work-places). In fact, at that time, albeit the enactment of that law marked a very important milestone indeed, it was a part of an ongoing process that had started some time before, in the ‘60s, with a number of statutory provisions granting labour protection: banning any interposition in 1960, dictating a very restrictive regulation of fixed-term contracts in 1962, protecting working women in connection with their marriage in 1963, providing compensation for unfair dismissal in 1966, long-term temporary lay-off insurance (“Cassa integrazione straordinaria”) and special unemployment benefits in 1968, issuing a very generous pension reform in 1969. A process of strengthening and improvement of the workers’ protection system that continued throughout three decades of so-called “flexible guarantee approach”, sometimes softening the protection granted in the “golden decade” ’60–’70, by adjustments, adaptations, but also reinforcing the protective system on some other occasions, like in 1990 in the field of individual dismissals, in 1991 concerning collective redundancies, in 2000 relative to part-time, in 2001 regarding parental leave. On March 2015, conversely, when the first two legislative decrees (n. 22 and 23) started enforcing the delegation-law no. 183/2014, and in June 2015, when a third very important decree (n. 81) followed, Italian labour law changed its fundamental paradigm: firstly, the property rule entailing employees’ right to reinstatement in their jobs in case of unfair dismissal, which had been a keystone of the system until then, has been now replaced by a liability rule, i.e. a rule limiting the employer’s contractual liability to the payment of an indemnification calculated according to the prevailing standards in Europe (decr. n. 23); secondly, it was introduced much more flexibility in personnel management in the company, which allows the employer a broader discretion in the adaptation of the employee’s duties to business needs (decr. n. 81). The unequivocal purposes of these changes are, on one hand, to provide the employer with a reliable forecast of termination costs, given that they have been already predetermined, and, consequently, to discourage any wager on the outcome of a lawsuit, which has pathologically increased litigation in Italy so far. On the other hand to pursue, through increased functional flexibility, an increase in labor productivity.Lets focus on the first point: the dismissals reform. From a system of sanctions aimed, apparently, to prevent unilateral termination by an employer, since the employees were assured that no forecast of the termination costs could be made by the employer, and that such costs were surely very high [1] [3], Italian law system has moved to a body of rules and sanctions inspired to a radically new design. The fundamental rationale underlying this new policy is to ensure possible predictability and at the same time to reduce termination costs, providing this is due to an adjustment of the workforce, a technological change, an organizational change, or the exercise of disciplinary power.

- The new rules on dismissals

The monetary amount of damage that can be obtained by an employee following to court action, has been determined by the new regulations to be equal to two months of the last compensation per year of service in the company; however, the minimum is four and the maximum twenty-four. Moreover, the same decree no. 23 of 4thMarch, 2015 – valuing the German experience – gives the parties the way of a standard settlement, so as to avoid litigation in court providing immediate payment of an indemnification equal to one month’s pay per year of service, anyway no lower than two months’ pay and no higher than eighteen months’: this solution is strongly promoted by the total exemption of this compensation from income tax.

The only cases left in which an employer is sanctioned by an order of reinstatement of the employee in his/her job are those of null and void dismissal expressly provided by law: unlawful discrimination, anti-union retaliation, working bride/mother in need of protection. Reinstatement is also ordered by the court whenever a disciplinary dismissal is then proved in court to have been grounded on facts that had never happened; however, the same provision expressly excludes reinstatement in the event that the court should deem the dismissal disproportionate to the fault of the employee, provided that a fault has actually occurred (in this case the court will sentence the employer only to monetary compensation).

The new dismissals discipline, which, not surprisingly, had strong opponents who claimed it was against the Constitution, can be explained within the new system frame created by the reform: in this new frame, reinstatement is no longer the main tool for protecting workers, since their economic and professional security will now be normally guaranteed in the market, rather than by freezing the employment relationship; conversely, the reinstatement will be a penalty imposed to the employer only in cases in which individual dismissal power be used in an aberrant way (meaning for aberrant use of dismissal power something quite different from mere debatable or missing justification).

- Overcoming the disparity between protected and unprotected employees

There were protests about this being a comeback of the Fifties, or even of the nineteenth century. On the contrary, what could be seen as a comeback of the weak regulations typical of the origins was the widespread use of long-term free-lance agreements, or other contractual types, which had been regularly used from the end of the Seventies onwards, with the purpose of circumventing labour law. A comeback of the nineteenth century were those three fourths or four fifths of fixed-term contracts compared to the general flow of new regular hiring, which characterized the Italian labour market in the last two decades.

The breakthrough has been made possible by the entry into force of the first two decrees of the delegation-law no. 183/2014. First, it includes a revival of the open-ended contract as normal form of employment, favoured by the law and encouraged by a strong tax break and welfare contribution reduction. Second, it creates a new focus of law-makers on the protection of the workers in the market rather than in the company at all costs, whenever they lose their jobs and have to seek for another, needing a reliable income support and – in many cases – strong welfare benefits too.

- Employees’ protection in the market, not against the market

The protection, hence, is no longer against the labour market, but in the labour market: thanks to a universal and egalitarian income support system, aligned to the best European standards, and to a restructured system of employment services (the latter, however, foreseen by the new legislative decree no. 150/2015, but still to be implemented).

The fundamental features of the new unemployment benefit scheme had already been introduced by law no. 92/2012 (the so-called Fornero Law). It has now been expanded in duration and extended to all unemployed people whose last job position be a subordinate employment –included relative to housekeeping and apprenticeship, which were previously excluded – or a relationship characterised by the economic dependence of the self-employed (although in this case a reduction of the unemployment benefit entity and duration is foreseen). Its coverage spans over the first twenty-four months of unemployment: in the first three months the benefit is equal to 75 percent of the last salary, then decreases by 3 percent every subsequent month, for a period of unemployment equal to half of the contribution period completed. To finance this, besides EUR 2 billion reserve per year, no forms of improperly applied welfare benefits will be admitted any longer, in particular the use of the so called “Cassa Integrazione” (a temporary lay-off benefit scheme, which was widely used beyond its institutional role) to cover unemployment situations.

The fundamental features of the new unemployment benefit scheme had already been introduced by law no. 92/2012 (the so-called Fornero Law). It has now been expanded in duration and extended to all unemployed people whose last job position be a subordinate employment –included relative to housekeeping and apprenticeship, which were previously excluded – or a relationship characterised by the economic dependence of the self-employed (although in this case a reduction of the unemployment benefit entity and duration is foreseen). Its coverage spans over the first twenty-four months of unemployment: in the first three months the benefit is equal to 75 percent of the last salary, then decreases by 3 percent every subsequent month, for a period of unemployment equal to half of the contribution period completed. To finance this, besides EUR 2 billion reserve per year, no forms of improperly applied welfare benefits will be admitted any longer, in particular the use of the so called “Cassa Integrazione” (a temporary lay-off benefit scheme, which was widely used beyond its institutional role) to cover unemployment situations.

Further to this sort of “first pillar” of unemployment benefits, the intention of the lawmaker includes a second pillar, consisting of supplementary unemployment benefits negotiated by collective bargaining inside companies, or even in the scope of every industry sector. 2016 Budget Law provides full tax exemption for this and other forms of “corporate welfare”.

- The so-called Repositioning Agreement as a tool to shorten unemployment spells

As regards the new system of employment services, the fundamental strategy conveyed by the delegation-law, enacted then by Legislative Decree no. 150/2015, is a strong integration between public Job Centres (PES) and private employment agencies (PEA), following the model successfully tested in the Netherlands. This complementary action is implemented by means of the new scheme of a so-called Repositioning Agreement, signed by the involved job seeker and the private employment agency chosen by the job seeker among a list of certified operators.

On one hand, the purpose of the Repositioning Agreement is to provide the involved job seeker with effective support for the successful repositioning in the productive fabric: providing this goal is achieved, and only after its achievement, the public job centre or the private agency is paid a monetary award, inversely proportional to the employability of the involved job seeker. On the other hand the involved job seekers are committed to keenly participate in all the activities proposed by their respective tutors as necessary for faster and better reemployment. Any unjustified refusal by the person concerned to participate in those activities, or any refusal of an acceptable job offer, shall be reported to the public service. Consequently, if the refusal were found to be unjustified, the unemployment benefit would no longer be paid.

This scheme is aimed to shorten the time of unemployment, and, moreover, exposes the unemployment benefit scheme to a fair system of “cross-compliance”: in fact, if an employment agency were known to be too strict, unemployed people would no longer choose it; if, conversely, its approach were too easy, it would not reach the goal of reemploying the job seekers involved, and would receive no monetary award.

As much as this might seem very close to a market mechanism, it is really needed to kick-start the performance of public job centres in their function of assisting and promoting contact between the unemployed and the certified agencies who can supply the intensive assistance service.

At any rate, there is no need to mention that a sharp cultural and statutory change is vital to the proper functioning of this new tool: so far, in the present Italian scenery those who benefit of unemployment welfare have rested on the serene certainty of being able to decide calmly whether and when to take action for seeking a new job, because nobody has ever checked either their action or their actual availability in the labour market. The Repositioning Agreement cannot be a successful tool unless this page is turned, both from a cultural standpoint and from the standpoint of labour law, leaving behind the current regime, which has provided practically unconditional income support up until now (only in favour of a privileged part of the unemployed, anyway).

The fact is, however, that this part of the reform has not yet been implemented: the new national agency, ANPAL, is expected to be operational only at the end of 2016.

- The new provisions governing change of duties and marking the distinction between subordinate employment and free-lance collaborations covered by the Civil Code

Another of the eight decrees of the reform is dedicated to the so-called “contracts reorganization” (legislative decree no. 81/2015), which is an important step on the way of simplifying legislation.

This decree includes, among others, a provision that grants more powers to employers to change their individual employees’ duties, as an alternative to lay-off: the new rule (which applies not only to new employment relationships, but also to those established before the reform) allows , in case of reorganization, the assignment of lower-level tasks.

The same decree also comprises a rule that redefines the border between the area covered by labour law and free-lance work area, only the latter governed by the Civil Code. Under this provision, labour law applies only in case the employer has the power to determine the place and time of the work performance. In other words, a warehouse operator or a secretary assistant can no longer be qualified as free-lance collaborators. Conversely, a journalist can still be classified as a free-lance collaborator providing he/she is free to work where and when they deem appropriate.

- The most significant issues of compliance with the Constitution: a) regarding the difference between the discipline of ongoing contracts and the discipline of new ones

The silver bullet of left-hand opponents to this reform is the claim that it is not compliant with the Constitution, since it implies uneven entitlements by employees as regards the regulation of dismissals, those under the old employment contracts and those under the new ones. This objection ignores that the existing situation was even less compliant, and this is why the present reform is willing to put an end to it. In fact the ancien regime practically excluded five-sixths of new recruits from the possibility to be hired under open-ended employment contracts.

Actually, on occasion to some other amendments of law provisions governing long-lasting contractual relationships, the Constitutional Court accepted both legal changes: those that had applied the new rules only to the contractual relationships established after the reform, and those that had applied the new rules also to pre-existing relationships, just limiting their application in the latter case, reasonably, so as to avoid a shocking impact of mandatory regulations on the pre-existing contractual balance.

On the other hand, in the case of this labour reform it is clearly reasonable to exclude those relationships that had been already established at the time of its enactment from the application of the new dismissals discipline. Just consider what might happen if the protection granted by the rigid 1970 discipline be suddenly removed for all employment relationships, both ongoing and new ones: this would risk to trigger the prompt dismissal of all the people whose employment balance be at loss to the employer, whether significantly or not, which so far have kept their jobs thanks to the old discipline. Should this massive layoff phenomenon take place, the economic system could by no means financially cope with it, since funds would not be sufficient to provide the necessary unemployment benefits to everyone. Neither by any action could the situation be faced, not even by the new employment services provided by the reform, such as the Repositioning Agreement, which requires cooperation between public services and specialized private agencies providing assistance to those job seekers who have just lost their jobs (see § 5). These new tools need a testing time, which is possible only if the demand of the new services is just gradually increasing over the first two or three years.

Furthermore, a sudden and dramatic increase of layoffs would provoke widespread social alarm, and, consequently, foreseeable pressure on the Government and the Parliament for suspending the application of the new rules. This would make employers and investors halt, facing an unpredictable scenario about the stability of the legislative framework, and would most probably neutralize the positive effect of the reform and its incentive to hire.

- Continued: b) regarding the replacement of the property rule that has protected regular workers so far, by a liability rule, and the reduction of Court-ordered indemnification; c) regarding the use of the predetermined severance cost as an objective sorting tool for business decision in this regard

The crucial political and juridical point of this reform is the transition from a regime in which a dismissal is considered a “death penalty”, or in any case a fact in itself pathological, only acceptable as a last resort in extreme situations, to a regime in which instead it is considered as an event belonging to the normal physiology of corporate life and also of any work career, to some extent useful for better allocation of human resources in the productive fabric, and, therefore, for improving labour efficiency and raising compensations.

The argument raised by the opponents to this approach may be summarized as follows: if a judge finds that the employer’s action was unlawful, why not to allow the same judge to sanction the unlawful action by eliminating in full its effects (reinstatement), or, at least, by ordering a compensation amount which be strictly proportioned to the damage actually suffered by the other party?

This is how that argument may be countered: firstly, it is worth noting that it is virtually impossible to quantify the actual damage caused to a dismissed employee, in each case, since there is no way to check on the actual availability of the same person for a new job and, most importantly, monitor his/her proactive search for a new job. Conversely, if the compensation is pre-determined by law, also based on the damage mitigation owed to the newly provided unemployment benefits, there is no danger that the prospect of a higher compensation obtainable through judicial litigation discourages the dismissed employee to take prompt action to seek efficiently for a new job.

Moreover, the most appropriate counterargument to the opponents to the reform is that no exact evaluation can be made in court since the depths of the expected loss which led the employer to decide the dismissal cannot be completely searched in a judiciary proceeding.

In truth, the reason for any dismissal has always been, ultimately, an expected loss in case of continuation of the relationship, whether in terms of financial costs or of opportunity cost. This also applies whenever the dismissal follows to the employer’s complaint for some fault of the employee. Thus, we are talking of the forecast of something occurring in the future, which cannot be proved in court, either by documental evidence or by witnesses: it can just be subject to an evaluation with wide margins of discretion. However, a court can hardly make such an assessment with reliable results, since a specific technical expertise and the knowledge of all context data would be required, none of which the court might have to the extent required.

The new rules governing this matter, hence, outweigh the impossibility of the employer to provide the court with exhaustive evidence of the economic reason or business cause for the dismissal, which is usually the case, except when a serious corporate crisis is manifest. On account of this, the new provisions offer a tool for sorting business choices in this field, based on a “standard termination cost” to be incurred by the employer whenever no agreement is reached with the employee on the termination of the work relationship. The sole exception to the above is the case in which the reason for dismissal is so evident that it can be easily proved in court.

In this view, most observers will find the rationale of the new Italian dismissals discipline consistent with the grounds of the draft reform of this matter that was presented to the French government by economists Olivier Blanchard and Jean Tirole in 2003 [2] [4].

- Impact of the reform on employment flows and quality in the first year

Law makers have helped the reform to take-off by a significant tax break and welfare contribution reduction for open-ended employment contracts entered into throughout 2015. More precisely,

- a) the Income Tax on Productive Activities (IRAP) was reduced for costs associated with new open-ended hires;

- b) the State takes over all cost of social security contributions related to new permanent hires, provided that they had not been employed under open-ended contract in the previous six months. The same incentive was provided in case of fixed-term contract converted into open-ended; conversely, it cannot be availed in case of apprenticeship converted into regular open-ended work agreement. In 2016, this economic incentive has been reduced to 40 percent of the amount of social security contribution due.

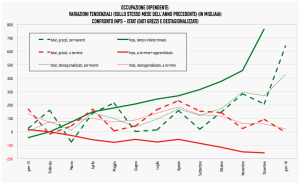

The following chart shows the data on the impact of this economic shock combined with the regulatory shock provoked by the reform throughout 2015:

Chart 1 – 2015 vs 2014 employment data trends. Source: www.lavoce.info

In the Economic and Financial Document submitted to the Parliament on April 9 the Italian Government indicates 846,498 as the difference between the new stable employment contracts (new open-ended hires plus transformations of fixed-term in open-ended contracts) and terminations during 2015.

During January and February 2016 we have witnessed a net decrease in new open-ended contracts: this is the predictable consequence of the peak of permanent hires which occurred in December 2015, caused by the December 31 deadline of the economic full incentive. However, if we consider the set of stable employment in the quarter December 2014-February 2015 (396,309) and the sum of those recorded in the quarter December 2015-February 2016 (543,119), we can agree that 2015 witnessed an increase of 37.0 per cent in open-ended hirings. And if we consider that in the months of January and February 2015, the full economic incentive was already in force, we can gain an indication of the causal link between the majority of the said increase and the regulatory shock.

Finally, the following data relative to the last quarter of 2015 show the impact of the reform on the labour market in term of decreased precarious work (fixed-term contracts and free-lance work agreements filling permanent job needs), since a broader area has been subject to labour law, in which workers are entitled to permanent employee rights.

People hired by open-ended employment contract in Q4 2015: 739,880 +100.9 percent

(doubled relative to Q4 2014)

People hired by long-term free-lance work agreements in Q4 2015: 104,676 -40.4 percent

(almost halved relative to Q4 2014)

Source: Min. Lavoro – Comunicazioni obbligatorie, March 2016 Monthly Report [3] [3]

- Hypothesis about the impact of the economic shock versus the regulatory shock

Now it is licit to wonder whether it was the regulatory shock (the new regulations on dismissals) or the economic shock (the significant tax break and welfare contribution reduction concerning open-ended contracts entered into in 2015 and continued in a milder form in 2016) which triggered the sharp increase of new permanent employment contracts in the year, i.e., 776,171 more in 2015 compared to 2014 (taking into account new hiring + former fixed-term contracts made open-ended, as we have seen in § 9).

Only by an econometric research this question can be clearly and plausibly answered. However, we already have some clues to hypothesize one answer at least, even if tentatively [4] [4]. The first clue is the balance between the increase in permanent employees hired in January-February 2015 compared to the same two months of 2014 (30.9 per cent) – which was affected by the economic shock only, since the regulatory shock had yet to come – and the increase recorded in March 2015 compared to March 2014(49.5 per cent), which was affected by both. This difference suggests that almost two-fifths of the increase was due to the new provisions on layoffs.

Another clue emerges from the comparison between the percentage rate of the overall increase in new open ended contracts or in temporary employees made permanent throughout 2015 compared to 2014 – 46.3 percent – and the percentage rate of the increase in apprentices made permanent under open-ended work contract, i.e., 23.2 percent. In fact, the latter was impacted by the regulatory shock only, not by the economic one. Based on this, again, a tentative assumption might attach approximately one half of the increase in permanent work relationships to each factor.

Moreover, we have seen (§ 9) that among the permanent employment data for the quarter December 2014-February 2015 and that for the quarter December 2015-February 2016 there has been an increase of 37.0 per cent, mostly due to the regulatory shock (since the full economic incentive was already in force in January 2015).

Finally it should be mentioned the figure provided by Istat [5] [5] and reported in the Economic and Financial Document submitted by the Government to the Parliament on April 9, according to which 35.1 percent of manufacturing companies and 49.5 percent of those in the service sector declared that they have been moved to increase the staff in 2015 also partly motivated by the new discipline of the permanent contract (those who declared they were pushed to increase the staff in 2015 also by the economic incentive are respectively 50.2 and 61.1 per cent).

The increase in new open-ended contracts will probably slow down in 2016, as a direct result of the economic incentive reduction. Nevertheless, it can be expected that in the medium term the positive influence of what we called regulatory shock will increase. In the first year after the reform has come into force, in fact, the impact of the regulatory shock has been surely mitigated by the justifiable scepticism of a number of entrepreneurs wondering whether the new regulations on dismissals could be counted on in case of litigation: they were still burned by the disappointing experience of seeing the new provisions by the so-called Fornero Law, no. 92 of June 2012, on disciplinary dismissals practically nullified by the courts’ decisions in the three following years. Now, instead, all operators in this field – including judges – confirm that in the first year after the new regulations have been applicable, almost every cases of early termination of employment under the regimen of the Legislative Decree no. 23/2015 have been resolved by means of standard transactions: which means that the 2015 reforms have produced the desired result of reducing drastically litigation concerning layoffs. This might convince even the most reluctant entrepreneurs to change the old practice of using a series of fixed-term hirings. This is why the impact of the reform should be stronger in the next months.

We have talked about flow data so far. What can be said about stock data? On this side there was an increase of about 300,000 jobs in January 2016 compared to January 2015, corresponding to almost 450,000 more employees (those shown by the thin green dotted line in the chart, taken from an article by Bruno Anastasia posted on www.lavoce.info) and almost 150,000 fewer self-employed people.

Will such employment growth continue?

Providing there are no negative impacts by exogenous shocks, there is good reason to hope that employment will continue to grow, because Italian consumers should be more confident of economic growth too, and international investors more willing to invest in our Country, as a result of the progressive alignment of the Italian system to the standards of other Western Countries with regard to labour regulations, performance of public offices and bodies – starting from the Courts – and energy costs. However, there is still that “providing”, which requires the utmost caution.

This article was released in June 2016

________________________

[1] In past decades, the cost to be borne by a company in case an employee won the lawsuit relative to his/her dismissal, pursuant to Article 18 of the Statuto dei Lavoratori, could raise up to a monetary amount equivalent to the compensation of the dismissed employee and welfare contributions for many years.

[2] O. Blanchard, J. Tirole (2003), Profiles of reform of employment protection regimes.

[3] The above data refer to Q4 2015 only, because – as we have seen in § 6 – the new boundaries of the area subject to labour law were laid down by a provision which became effective in July 2015 only (its consequences, hence, could be seen only in the last quarter of the year).

[4] P. Sestito and E. Viviano (Hiring incentives and/or firing cost reduction?, Banca d’Italia March 2016) arrive at different conclusions about the distribution of the causes of the increase in permanent employment contracts between economic shock (40%) and regulatory shock (5%). But they reach these conclusions on the basis of the observation of what happened in the sole Veneto Region (about one tenth of the entire Italian population), and only in the first half of 2015.

[5] Istat, Rapporto sulla competitività dei settori produttivi, February, 2016, http://www.istat.it/it/archivio/180542 [6]

.